The Promise of Education Technology

Around this time last year, I was chatting with one of my friends about the recent trend of college hackathons and he blurted, “wouldn’t it be awesome to have a hackathon at the white house?”

Around this time last year, I was chatting with one of my friends about the recent trend of college hackathons and he blurted, “wouldn’t it be awesome to have a hackathon at the white house?” We talked about it a bit before getting back to our homework.

This is the transcript of the TEDx talk I gave at UCSD.

I am a computer scientist by training, but as someone who has been in school for the majority of my life, I’ve spent a good amount of time reflecting on my own education. For a long time education and technology have been separate disciplines, but as technology is increasingly incorporated into every area of our lives, education also increasingly incorporates technology.

How We Got Here

In the spirit of getting teaching and learning into the digital era, we’ve tried many different ideas to make education more digital. 2012 was the year of the Massive Open Online Courses (also known as MOOCs), and promises to make learning, faster, cheaper, and better scaled to students everywhere. The result? Teachers recording lectures the same way they would give them in a classroom, putting them online, resulting in completion rates of about 15%.

In 2013, LA unified school district planned to spend $1.3 billion on iPads, only to turn around on cold feet after realizing that the software and infrastructure wasn’t what they thought they signed up for.

Despite these failures, there are also many instances of technology having a significant positive impact on education. Students all over the country are using technology in their education, in everything from research to video projects to computer science.

Albemarle County Schools in Charlottesville Virginia is one example among many pockets of primary and secondary schools that have received national acclaim for the success of their makerspaces, inspiring many of their K12 students to use creative technological mediums to share what they’ve learned.

And through the ConnectEd initiative of the Obama administration, more schools in the US are providing internet access to their students than ever before, helping students to prepare themselves to work with the digital tools that are ubiquitous today.

But as the test scores of our nation has fallen far behind those of China, Singapore, Japan, Korea, and Finland, people are justified in pointing out that our efforts with education technology have not given us the results that our technology had promised.

Technology was supposed to improve education by making it higher quality, more accessible, and more affordable. But while technology has improved education for some, it hasn’t been as successful as we’ve been hoping for as a nation.

What happened? Wasn’t technology supposed to come in as the grand superhero and solve all of our problems as it did for so many other sectors? As a Silicon Valley native, I wondered: what would it take for technology to disrupt education?

Down the Rabbit Hole

Pondering this point for myself, I went on a journey to learn as much as I could about our education system, venturing far outside the perimeter of the technology sector.

Remember that conversation about hackathons we had? In September of 2015, my friend became an intern at the White House and I started interning at the US Department of Education. I couldn’t believe it.

But that was only the beginning. How would two interns convince senior staff to let us host such an event? Interns don’t just come in and tell people what to do. And the prospect of hosting a “hackathon”, a type of event rather foreign to public officials, would prove to be a very difficult task. The White House doesn’t even have Wi-Fi.

After brainstorming some ideas only to have them sit on the desks of white house staff, we had a better idea: what if we did it as a part of CS Education Week?

On December 7th, 2015, we welcomed teachers, developers, and students to the white house for a CS Tech Jam as a part of Computer Science Education week. Participants had a simple goal: to start something that would improve CS Education in America’s public elementary schools, addressing early STEM biases that keep girls and minorities out of computer science.

We brought in teams from Sphero, Glasslab Games, Magic Leap, Google, and more along with local high school and college students and teachers from all over to US.

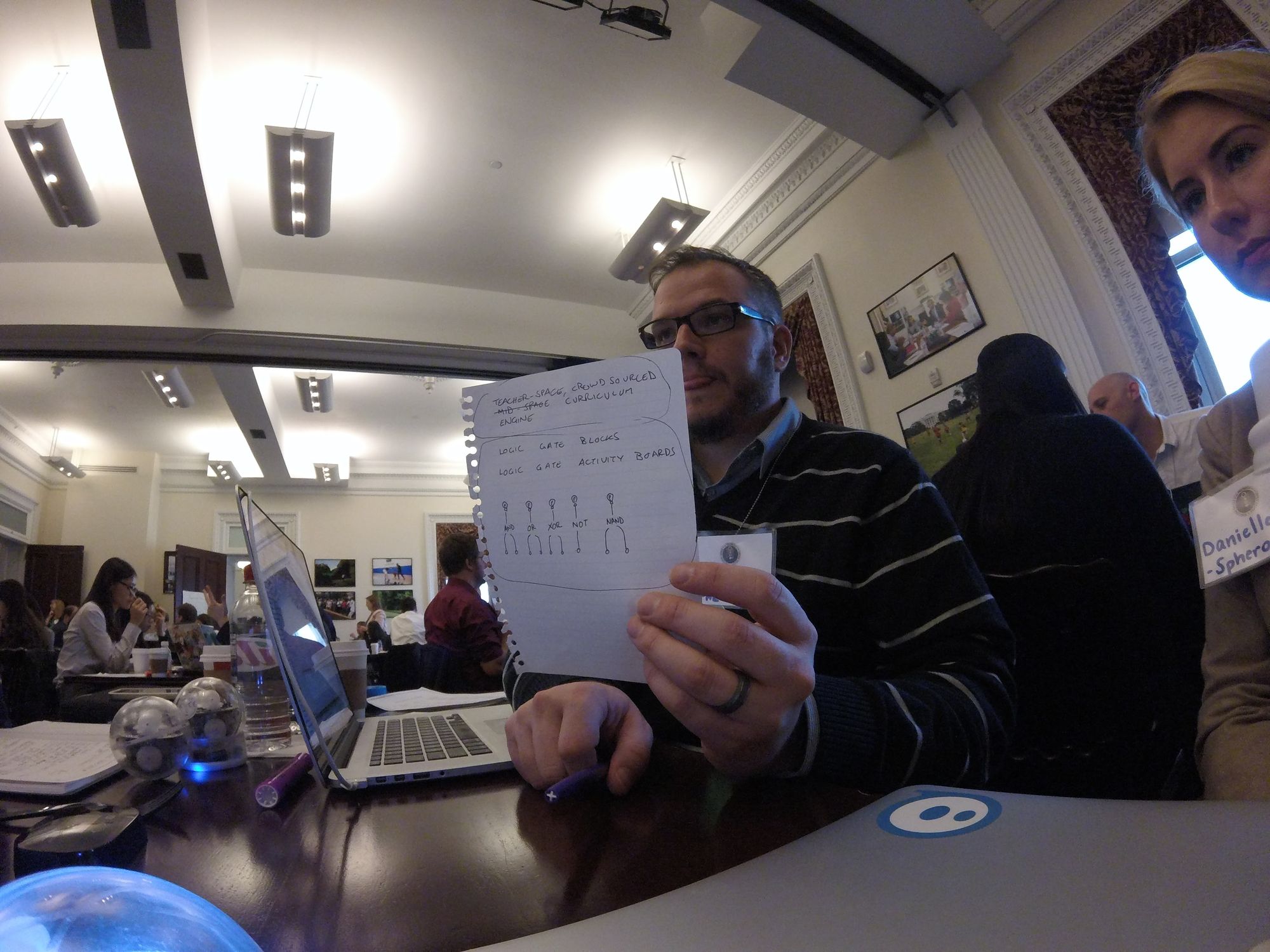

Projects at the tech jam included a simple game to programmatically play chutes and ladders, a game to learn about logic gates, and an instagram-like app that allowed users to upload code that rendered into artistic animations.

This is a picture of the team from Magic Leap brainstorming with a few teachers.

This is the team building the game for students to manipulate logic gates.

By bringing together tech companies, teachers, and students, all voices were critical in creating something that would truly be effective. It was in that moment that I had a key realization about education.

John King, the current secretary of education, in a closing address at the tech jam that we hosted, spoke about the importance of bringing all stakeholders into the conversation.

“I was encouraged by the level of listening that was taking place. As I visit schools around the country, too often you see technology tools that might have made a difference in theory, but aren’t actually working for kids in the classroom.” – John King

That day showed me that it was the dialogue between students, educators, and developers that become powerful ideas for education. When we come to the table willing to listen and understand, we are able to personally invest ourselves in a mission that isn’t just about us, but about fundamentally adding value to the people we are serving.

But what does this have to do with technology?

The Conversations in Edtech

The legend of Silicon Valley, Steve Jobs himself tried many things to improve education with technology.

“I used to think that technology could help education. I’ve probably spearheaded giving away more computer equipment to schools than anybody else on the planet. But I’ve had to come to the inevitable conclusion that the problem is not one that technology can hope to solve. What’s wrong with education cannot be fixed with technology. No amount of technology will make a dent.” – Steve Jobs

The three months I spent at the department of education gave me a bigger picture of the incredibly diverse set of issues that our education system in the United States faces that is unique to our own country. Not only do we have students of every single racial and cultural identity, we have to address different languages, social norms, and expectations.

Steve Jobs was correct given his assumption of education, but his assumption was fundamentally flawed: He approached education technology as a charitable donation that he hoped would automatically improve teaching and learning. But simply giving a student a computer doesn’t mean that their grammar is going to automatically improve.

Contrary to the ethos of Silicon Valley, education can’t be disrupted with a single solution. With so many different stakeholders in such complicated dynamics, getting technology implemented in education isn’t about companies developing and pushing their ideas, but about the conversations with everyone involved: students, teachers, administrators, developers, and more.

It’s about understanding the problems and utilizing technology only when it is the best tool for the problem. With so many diverse problems in our education system, improving education with technology starts with understanding the types of problems students face on a regular basis. Too often we forget to consider how our decisions impact students of lower socioeconomic statuses, minorities, and other marginalized students.

In contrast to Steve Job’s statement of using technology in teaching and learning, former secretary of education Arne Duncan framed it in the context of technological access.

“I worry that technology is not being implemented fast enough. Technology has the ability to improve equity in our public schools, or the ability to exacerbate current equity gaps.” – Arne Duncan

Trying to unify the two perspectives led me to my next question: Given that we can’t make assumptions about the solutions that students need, what are the problems that all students, especially disenfranchised students, struggle with on a regular basis?

Listening to Students

To answer this question, I turned to the tools I know best: web programming. I started thinking about technology in a different way; not just technology as a potential to augment teaching and learning, but as a means of civic engagement and empowerment.

With a student run nonprofit named Student Voice, I got together with a group of friends and put together the Student Bill of Rights, a collection of 12 rights covering everything from free expression to health and well being to technology.

Then, in order to allow students to share what matters most to them, I built a voting platform around the 12 rights and allowed students to vote on the three rights most important to them.

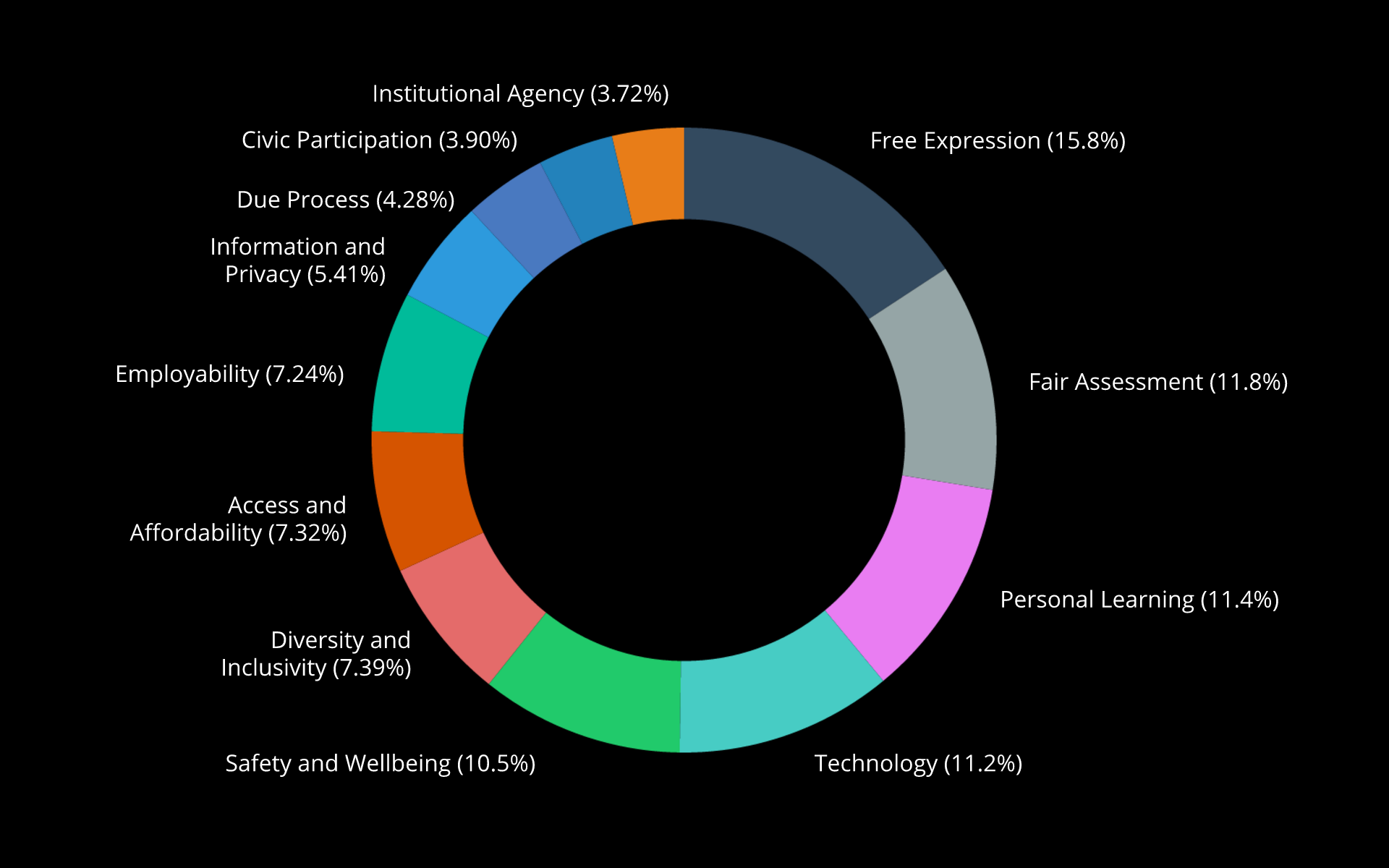

Here is what we found: Of over 1000 students who voted, the most voted on right was free expression, followed by fair assessment, and personal learning. What all three of these have in common is the emphasis on the students. Students want to express themselves, to be understood, and to make education their own.

And yet, in an effort to make high school graduates more “college and career ready”, students are increasingly taught to fulfill educational standards in compliance with No Child Left Behind and Common Core, which inherently detracts from a student’s ability to personalize their learning.

And even some of the technological pushes in education have been nothing more than putting lectures online, worksheets in a digital format, and multiple choice exams on a screen. It is this lack of personal agency that is reflected in the voting results.

Perhaps the first responsibility of our education systems is to listen to our students.

To make the quantitative qualitative, we paired the digital voting with a national tour, visiting schools all over the country. On our national tour, Andrew Brennen, the National Field Director for Student Voice, took the step to listen to students and their stories. Here are a few of them.

“Our field trip account is zero. Our activities account is zero. We keep getting told that all of our money is in the general fund and can’t be used for things like textbooks or paper. This general fund seems great though, some mysterious crazy place. How can I get some of this general fund?”

This next story, from a refugee student belonging to a group where students openly share stories, showed me the importance of allowing students to freely express themselves before they can be comfortable in their classrooms.

“…After my dad died I was so depressed. I could never leave my house. I could never talk to anybody. But when my mom said let’s go on vacation I was feeling like sure. So we went but then when I saw the border I was like wait where are we. After that my mom said we were going to the US and I was like, “What? You never told me that! You never told me anything!” And I start crying more and more and more. I hated my mom for those fifteen days because she never really told me what was going to happen but at the same time I feel happy because if she would’ve told me, I would never have come with her. I got here legally. One of the happiest things when I got here was that I got to meet my uncles and my grandpa. Those people were never in my life before but now they really help me out.”

These are only a few of the many incredibly personal stories that we’ve collected and shared through our online platforms. And hopefully by getting a small glimpse of what students go through on a regular basis, you’ve come to a similar conclusion that I did: Maybe we’ve been looking at education technology wrong this whole time.

Technology shouldn’t be a sterile, programmatic medium for students to standardize their learning. It needs to be a tool that allows them to further express their creativity and emotions in a safe way. I don’t see the journey of education as a deterministic computation, I see it as a beautiful mess of emotions, struggles, and community.

Students are people full of ideas, emotions, problems, character, nuance, culture, ambitions, and thoughts. Students spill out in ways that don’t fit within conventional boundaries. Just look at student organized movements like the Vietnam war protests, demonstrations against genocides overseas, civil rights and black lives matter – students have always been at the forefront of taking action to be the change they want to see in the world.

I’m not saying that protests are the only way to improve education, but we do need to be heard. Education is not the responsibility of the government, nor is it the responsibility of the teacher. It is the responsibility of the whole community: students, teachers, parents, and educators to dialogue about the things we can do to improve our schools, our country, and the world.

The ways that students have organized looks vastly different from generation to generation, and as our generation sets the example for what it means to bring equity and equality in our technological age, I hope that you are as proud as I am to be a student attending school in America today.

As students, we are all inadvertently part of a dialogue that transcends our education systems, whether we are aware of it or not. It is through this dialogue that we have the choice to empower or silence the voices of the students around us. It may be hard to believe that your voice matters in the big picture of education, and that’s how I felt before organizing the White House Tech Jam.

Education has a long way to go before we solve the problems of quality, equity, affordability, and accessibility. And whether we achieve those solutions through technology or otherwise, it begins with students like us participating in this dialogue. How will you participate in this dialogue?

I’m going to leave you with a confession:

I started this journey thinking it would be about technology, but it’s not about the technology; it’s about the student.